Excerpt from Heidegger’s Hermeneutics (PRAV Publishing, 2025), translated by Jafe Arnold.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the concept of “event” and semantically analogous terms became central to many philosophical systems of diverse tendencies. In the 1860s-70s, in the neo-Kantian school, the concept of the “subject” was reconceptualized in such a way that both “subject” and “object” ended up being two poles of a certain original reality, like the positive and negative poles of a magnet (an image proposed by Otto Liebmann). It subsequently became commonplace for philosophers to seek out a certain primal reality that precedes both subject and object and contains them as if in “collapsed” or “compressed” form. In Ernst Mach’s empirio-criticism, this reality was the “neutral elements of experience,” in William James’ pragmatism “pure experience,” and in Bertrand Russell “logical atoms.” Both Heidegger and Ludwig Wittgenstein, seemingly independently, came to designate this supra-subjective and supra-objective reality, which, of course, they understood differently, as “event.” In their wake, “event” came to occupy such a central and enduring place in the problematic of different tendencies that the philosophical situation of the mid-20th century could be called a “battle for the event”. Concurring that it is precisely “event” that should be at the center of philosophical discourse, various philosophers debated what an event is, what its ontological and gnoseological status is, and how it can be rendered intelligible. Besides Heidegger’s hermeneutics, this notion also occupied a central place for Alfred North Whitehead, who created an entirely distinctive form of “new metaphysics,” “event metaphysics,” as well as for Gilles Deleuze, who interpreted this term in a Postmodernist vein in his Logic of Sense.

In Heidegger, event and meaning are categories of the same order, almost identical. Both of them annul subject-object duality: while thought is inherently subjective, meaning is not; Being can be “objective,” but an event can not.1 Both event and meaning are real from the perspective where the observer is simultaneously the creator of the observed picture and a part of it.

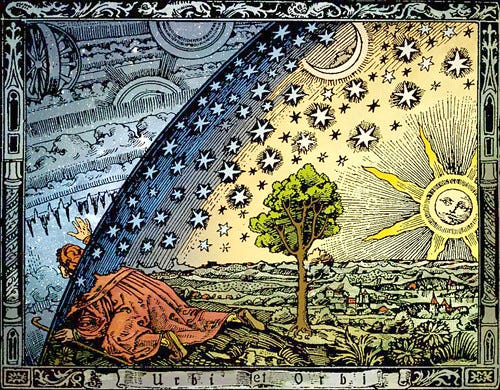

Event is a form of the existence of meaning, a unit of meaning, an “atom,” like Leibniz’s monad or Democritus’ atom. Insofar as there is no category in hermeneutic philosophy that is more primordial than meaning (even Being is one meaning which Dasein imparts to beings), event can be deemed an “atom of the cosmos” (if, like Democritus, we admit the existence of atoms that are “as big as the world”).

An event is indelible not because it is impenetrable to other events, and not because it itself cannot be divided — it can; rather, it is because it loses meaning upon division, collapses into nothing, and therefore dividing it is meaningless and inappropriate, regardless of our intent.

Being and time “come about” (are gathered together) in event. Event gathers the world. But what gathers and maintains the parts of an event (the “subjective,” “objective,” and others)? What is the gathering legein? What is the spark which suddenly dashes between its parts? What grants the ground of its unity? Such cannot be the unity of the subject or the unity of the object, nor can it be spatial or temporal unity, since all of these concepts are derivative of the Event itself. In order to answer this question, even in part, let us examine the relation between event and time.

The peasant plowing his field in spring is the peasant from the future winter who wants to be well-fed, or an emissary of the latter. He is a worker from the future (not a “guest from the future”). One could, of course, protest: How can we, in the present, distinguish when we are “emissaries from the future” and when we are merely acting on the basis of our ideas about the future? After all, would the peasant be in error if he were sowing at the foot of a volcanic mountain and did not know that his crop would be destroyed by an unexpected eruption?

We are misled by the old division of time into past, present, and future, against which Augustine had enough to say. The event that we call “future” is supra-temporal or “always in the present” — in its present. The participants who find themselves inside an event experience it as unfolding in time, but, once again, in its — the event’s — time. Then, when the participants get out of the event (and this is possible only through death, whether in the greater or lesser sense), they can try to grasp it in its totality. But the event “was,” and was “always,” integral; it is whole. This is precisely Augustine’s understanding of eternity in its relation to time. In Heidegger’s terms, we could express Augustine’s thought very precisely in the following way: eternity is the “event (Ereignis) of the world.”

Heidegger’s innovation lies only in recognizing that events, like Leibniz’s monads, are manifold: there are many events, including smaller ones that merge into larger ones and might seem to be limited within the time of the larger event. But an event cannot be limited by any time, just as volume cannot be limited by a line. Every event is a possible center of history, an event of events, in relation to which all of the past is pre-history and all of the future is the consequence, the unfolding. Therefore, just as in Leibniz every monad reflects the whole Universe, only with differing degrees of distinctness, so does every event encompass all time and all of history, but in different perspectives and different degrees of “distinctiveness.”

Therefore, when the peasant is plowing his field in spring, he is not an “emissary” of a winter that still has yet to arrive — winter has already “onset” in his plow, along with summer and autumn. If the earth’s axis suddenly turned and winter did not arrive as usual, and instead an eternal spring did, this would not mean that the peasant was wrong in his calculations for winter. It would only mean that the event of “winter” was limited to the premonition of the caring plower. The same goes for the sultry wind of the desert that usually forebodes a sandstorm: it can, of course, change, but it is not only a sign; it is already part of the storm, and in it, the storm has already begun to come about (just as Gorky’s petrel, a bird which in Russian is called a burevestnik, a “storm-herald,” is part of the storm, its outer frontline unit and reconnaissance agent).

Heidegger’s “History of Being” sees only Events, not facts or incidents. The significance of historical Events is like the meaning of signs and things. Just as meaning is the articulated and differentiated meaning for outward expression, so is significance an event in its projection upon other events.

The connection between events in history is semantic, not causal, or more precisely, it is “significant,” since the category of “causality” has application only within time, whereas the category of “significance,” like “meaning,” is outside of and above time.

Events form contexts, in which they fulfill the role of signs. They remain internally self-sufficient, but they are “drawn” towards each other (in semantic space) by greater events to which they are hierarchically subordinated (which they “enter,” “become part of ”).

Signs obtain meaning only in context, from other signs. Events obtain significance only in history, from other Events.

Before the Turn, Heidegger already proceeded from the premise that a sign has meaning only in context. Now it bears clarifying that a word, as an Event, has meaning in and of itself, but has significance only in context.

Future Events might be significant for past Events to a greater or lesser extent, or vice versa. For example, the repentance of a sinner (as in the Biblical parable of the prodigal son) imparts meaning to past wanderings of the soul, i.e., it is significant for them; if there had been no repentance, they would remain meaningless. But the converse, i.e., that the repentance would obtain significance only from past sins, would not be true: repentance has its own, “irreducible” meaning whose context is broader than the sins preceding it.

The time of history is, once again, “intra-event time,” and history itself is constituted by some great Event that opens up space for lesser Events to come about and become the subject of history. Therefore, history must have a beginning and an end — not because historians change or we lose interest in history, but because the event at the core of history is a whole, which means that it has its own limits. And we “historical people,” moving within the time of a still greater Event, leave the Event of history through our own transformation, that is, death in the broad sense. Thus, history is fulfilled, which is to say that it is finished, for it has come about.

Heidegger endeavors to hermeneutically uncover the Events that lie at the core of, first, European history in general, and second, the history of the modern era (“New Time,” Neuzeit) in particular.

In the modern German language, the word Ereignis means “event,” and is synonymous with Geschehen, which means“event,” “occurrence,” “incident.” This term drew Heidegger’s attention because “event” pertains to history, and because “historicality,” which the philosopher discovered in 1924 in the correspondence between Dilthey and Count Yorck, became a “guiding star” for Heidegger’s philosophizing. Moreover, unlike Geschehen, Ereignis harbors the very significant root Eignen, which unites this word with a whole circle of words that share this root. In the lecture “On Time and Being” delivered in January 1962, Heidegger spoke of “bringing into view Being itself as an event.” As always, Heidegger has to expend great effort on overcoming the ordinary metaphysical “hearing” of words: “In the phrase ‘Being as Appropriation [Event],’ the word ‘as’ now means: Being, letting-presence sent in Appropriation [Event], time extended in Appropriating [Eventing]. Time and Being appropriated in Appropriation [Event].”2 Since Heidegger is here relying, even more so than in other cases, on the root Eignen (“appropriating,” “own-ing”) resounding in Ereignis, the Russian translation does not convey the “intrigue” at play in Heidegger’s thinking, while the existing English translation outright puts “Appropriation” instead of “Event.” In Russian, there is a potential interplay of meaning here between the word for “Being,” bytie, and the word for “event,” sobytie (so-bytie, “with-being,” cf. Mit-Sein), which could also bring into play the Heideggerian notion of “gathering” (sobiranie): “event” (sobytie) is “Being” (bytie) in gathering (sobiranie), i.e., “Being together.” Since the term “event” occupies the place of the main subject of hermeneutic interpretation in the last period of Heidegger’s works, this period is the most difficult to understand on the basis of translations. Here, Heidegger recognizes that “overcoming” is always conditioned by what is being overcome:

To think Being without beings means: to think Being without regard to metaphysics. Yet a regard for metaphysics still prevails even in the intention to overcome metaphysics. Therefore, our task is to cease all overcoming, and leave metaphysics to itself. If overcoming remains necessary, it concerns that thinking that explicitly enters Appropriation [Event] in order to say It in terms of It about It.3

The term “event” has its own history in Heidegger’s philosophizing: before Ereignis came to be put in the place of “Being” itself (as the subject of hermeneutics), Heidegger spoke of “events” in the “onto-history” (History of Being) of Western European mankind. The main “event” that has determined Europe’s fate is the “oblivion of Being.” The “events” of this history include the reconceptualization of the essence of truth in Plato’s image of the cave, the victory of method that culminated in the philosophy of Modernity, the “death of God” in Nietzsche’s philosophizing, and the “unbridling” of metaphysics amidst the dominance of modern European technology. Furthermore, we can also presume that Heidegger considered his own philosophy to be an expression of a certain “turn” in the onto-historical fate of the West, a turn towards thinking Being. It follows from the picture of the “History of Being” drawn by Heidegger that the “event” of Heidegger’s philosophy wields significance of the same order as the event to which Plato’s dialogues testify: the epoch of the dominance of metaphysics began back then, and now this era is ending. Western European history began back then, and now it is ending, passing into world history.

According to Heidegger, the very notion of history becomes possible only in the epoch of metaphysics, when Being (Event, Ereignis) has been forgotten, leaving only the collecting of exterior, secondary events (“incidents,” Geschehen). Before the emergence of metaphysics, the main participants and creators of events were gods and heroes; in history, there are historical actors. Heroes know the omnipotence of the gods and follow their duty and nature, and even the gods follow the necessity of fate, whereas the actors of history carry out the expansion of their personality, which, if circumstances allowed, would be limitless. History is derivative of metaphysics (the oblivion of Being) because it is the indiscriminate collecting of accounts, which means that it does not take into account the ontological (existential, divine) dimension of events. History did not exist before metaphysics, for time was perceived in different perspectives, such as in the dimension of myths, legends, and tales.

For Heidegger, the beginning of history coincides with the “beginning of Europe.” The essence of Europe is irreducible to geographical determinations, for it is an onto-historical category: the domain of space and the interlude of time are caught up in the whirl of the “Event of metaphysics” as the “oblivion of Being.” For Heidegger, the “beginning of Europe” coincides both in time and in meaning with what Karl Jaspers defined as the “axial age” of world history. For Jaspers, the “axial age” is the moment of the emergence of history and is marked by three processes (or “Events” per Heidegger) which have defined the life of European mankind over the entire course of its history to the present. The main historical markers of the “beginning of Europe” (the “axial age”) are:

in social life: the collapse of the traditional tribal structures of society and their replacement by civil (legal) ones, a consequence of which was the formation of empires;

in religion: the formation of monotheism, the crisis of ritual religion, and the development of the religion of moral self-consciousness;

in philosophy: the emergence of metaphysics, the division between the speculative and sensory worlds, theoretical and practical orientations, and true knowledge and opinion;

the emergence of science as a consequence of the metaphysical approach to comprehending actuality, the practical component of which, technology, emerges as a means of subjecting actuality to the metaphysical “project” (the “world picture”).

The axial age is only the peak of the spiritual restructuring that took place in the three cultural centers of Eurasia –China, India, and Greece – all of which, however faintly, were engaged in interaction with each other. This spiritual restructuring initiated a shift in thought and in the conditions of material and social life. Over the course of 2,500 years, this movement spread and deepened to the point of becoming worldwide in breadth and conscious of its own essence in depth (in order to be conscious of the significance of the axial age, one needs to see it from a distance of 2,500 years).

The modern epoch also recognizes itself to be a new “axial age.” Some have associated this with the astrological cycle of the procession of the Earth’s axis (the past “axial age” coincided with the Spring Equinox entering the constellation of Pisces, whereas now it is entering the constellation of Aquarius). The significance of the threshold at which mankind stands now incomparably exceeds the “axial age” of antiquity, because never before in its history has mankind stood on the precipice of the real threat of the annihilation of life on the planet. Do we have any grounds for optimism? The emergence of the noosphere might, of course, proceed through various crises and turning points, but the logic of the development of nature suggests that development cannot break off on this level. In its actions henceforth, humankind on this planet must take into account not only momentary benefits, but far-reaching consequences and prospects, i.e., it must become the subject of planetary, cosmic, and self- consciousness. Mankind, awakening from the “oblivion of Being,” must be conscious of its connection with all beings and its responsibility before them, and cease to be guided solely by whatever is “visible” on the surface of beings. Mankind must lead its life in accordance with the “call of Being.” Of course, Heidegger does not clarify what expressions this might take on, since the event of the “oblivion of Being” is far from ending, and the “end of metaphysics” itself might make up an entire era, but in the depths of the onto-history of mankind, this event has already begun to yield to a new one. Accordingly, a new era has begun to “take the word” in the language of the “essential poets” and thinkers, and everyday human existence is inevitably tuning in to the “main tone” of the event resounding through it.

If history became possible only with the beginning of metaphysics, then it is obvious that the end of metaphysics should mean the “end of history.” But, interpreting Heidegger’s thought, in what sense can we speak of the “end of history”?

History is now ending because space-time has shrunk to such an extent that collecting data on events is no longer necessary, as an overwhelming amount of information and events are constantly bombarding humanity. On the other hand, the scale of events has become so fine-grained that even the death of the world will hardly hold as much significance for us as, for example, the Olympic Games did for the ancient Greeks.

Hence, it is necessary to take into consideration how the word “history” is used in several senses:

The past in general (“natural history,” the history of the evolution of man, etc.).

The past as covered by written documentation (Jaspers).

History as a science that collects noteworthy facts and occurrences to satisfy the curiosity of future generations.

History as the unfolding of events, an unfolding which is not defined by man even though it consists of the sum of human actions (“getting caught up in history”).

History as historical self-consciousness: man is conscious of himself in the context of a particular, unrepeatable era and is conscious of the impact of the past as well as the impact on the future.

History-1 cannot end as long as the world physically exists. History-2 cannot end because it does not exist “objectively,” as it is a fiction of “historical consciousness.” History-5 cannot end because it has not even begun for all people, only for rare thinkers who rise up to philosophically think the human past. History-3 and History-4 are tightly bound up with metaphysics because both proceed from the metaphysical preconception that an “event” is an instance, a fact, a recorded given that is accessible to all. However, genuine and definitive Events are not universally accessible, and yet it is these Events that are necessary to study first and foremost in order to understand the past. History-3 and History-4 will end when man wakes up, becomes conscious of the main Events, and becomes a conscious actor on this dimension, a “co-worker of evolution” (according to the Russian Cosmists, this is the main predestination of mankind, and its actualization is evolutionary inevitable).

What will become of the world after the end of history? Will it die? This, unfortunately, cannot be ruled out, but it is by no means predetermined by the end of history as such. Just as before the beginning of history, man will live in different dimensions of time (different forms of perceiving and experiencing time). Which dimensions? Heidegger leaves this question open.

***

READ MORE: Heidegger’s Hermeneutics (PRAV Publishing, 2025), translated by Jafe Arnold.

In Russian, “event,” sobytie, appears to be so-bytie, “with being,” i.e., German Mit- Sein, but given that we are following Heidegger’s thought as expressed in German, we shall leave this association, even though it virtually begs itself, outside of the “playing field.”

Heidegger, On Time and Being, trans. Joan Stambaugh (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1972), 22; idem, Vremia i bytie. Stat’i i vystupleniia, trans./ed. Vladimir V. Bibikhin (Moscow: Respublika, 1993), 404.

Heidegger, On Time and Being, 24; Vremia i bytie, 406.