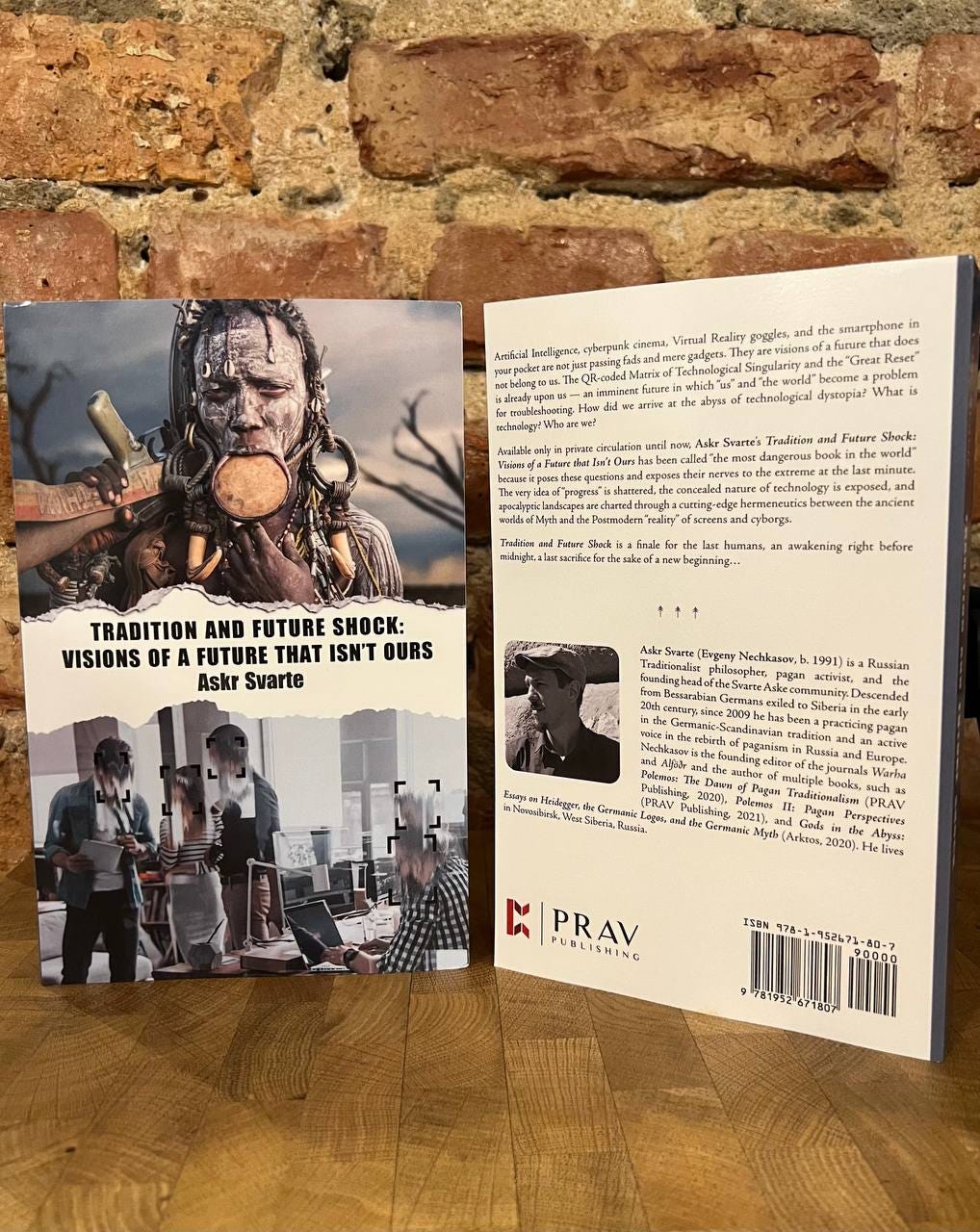

Askr Svarte [Evgeny Nechkasov], Tradition and Future Shock: Visions of a Future that Isn’t Ours (PRAV Publishing, 2023) + 20% discount code for subscribers below

The Thing

“Science's knowledge, which is compelling within its own sphere, the sphere of objects, already had annihilated things as things long before the atom bomb exploded.”

– Martin Heidegger, “The Thing”1

“The machine does not create new riches. It consumes existing riches through pillage, that is, in a manner which lacks all rationality even though it quickly employs rational methods of work. As technology progresses, it devours the resources on which it depends. It contributes to a constant drain, and thereby again and again comes to a point where it is forced to improve its inventory and to rationalize anew its methods of work.”

– Friedrich Georg Jünger, The Perfection of Technology2

Science, like a strict watchman, only allows into its domain whatever fits its harsh rules. As Friedrich Georg Jünger wrote in his fundamental work, The Perfection of Technology, “Where [technology] becomes dominant, it produces a mechanical order akin to it; it brings to the fore a watchmaker mentality.”3 The thinking of the technician constructs a world out of the measurable and explainable, out of what is subordinate to the general order of measurably flowing mechanical time, leaving out everything that defies its method. The thinking of the technician is directly connected to the concept of the Gestell. In this lies its deepest limitation of thinking, its compelled blindness to the fullness of Being.

Imagine a cup in front of you, full of dark, thick wine, sparkling with ruby reflections in flickering candlelight. You can smell it and anticipate its tart tase, but scientific objectivity turns the cup into an empty geometric shape and the wine into a “faceless” liquid, a substance with a specific chemical composition subject to the strict laws of physics. Poetry disappears, replaced by formulas and graphs. The thing itself, with all of its captivating, mysterious appeal, does not exist for science. All that is left is a pale shadow of the thing, lifeless, devoid of beauty, grace, and poetry.

This is how science strives to know the universe. But can one know the universe by denying the very essence of life, by turning it into an empty set of abstractions, bare schematics, and absolutely nominal signifiers? In his pursuit of the objectivity of the scientific worldview, isn’t man missing what is most important — the soul of things, the trembling of mystery, and the depth of thinking of das Geviert, the “Fourfold” through which Seyn-Being lets itself be known?4 The answer to this question lies beyond the confines of positive scientific discourse — as does everything else that we we have to say. The answers are to be found in the realm of the subtlest spiritual intuition, which, of course, does not in any way devalue these ideas themselves, but undoubtedly incites skepticism in the eyes of positive science — from the point of view of the scientific worldview, whatever cannot be empirically proven simply does not exist.

But what is interesting is that philosophy falls out of the general list of “sciences,” and some thinkers see the unrestrained development of technology as anything but a blessing. Friedrich Georg Jünger noted that striving towards endless improvement and detailing is inherent to technology, and he contrasted technical perfection (Perfektion) as a kind of unfinished process to the fullness and completeness of Being (Vollkommenheit).5 Technology, thus, is complete privation and emptiness.

Technology by its very nature is hungry. Jünger describes hunger as the foundational quality of technology: “The machine gives a hungry impression. And this sensation of a growing, gnawing hunger, a hunger that becomes unbearable, emanates from everything in our entire technical arsenal”.6 Wherever progress has set foot, there is henceforth a silent, endless desert, a memorial to titanic hubris and the insatiable greed of mechanisms.

Jünger and Heidegger’s insight into the fate of technology has proved to be extremely penetrating. However, let us pose the question to ourselves: are there any thinkers alive in the modern world who, in the current moment, are capable of thinking through the impact of technology on human existence? How many of them are there in such an era when man is increasingly becoming an appendage to a machine, and Being is dissipating amidst indistinguishable streams of information? Are there any surviving islands of genuine thought and the capacity for philosophical questioning that can resist the total oblivion of Being?

In contemporary conditions, belief in progress has turned into an indisputable dogma, and few dare to doubt its benefits. Most people perceive new technologies as a positive result of infinite growth (the belief in which is itself illusory), and technological achievements are seen as a symbol of national pride and superiority in the world arena. This almost religious faith in scientific discoveries is based on the myth of endless progress and the blind hope that tomorrow will be better than yesterday, while the past is seen as mere prehistory, as a dark age of ignorance that has been overcome for the sake of creating this brave new world.

Evgeny Nechkasov [Askr Svarte] is one those few contemporary thinkers who possesses independence, depth, and sobriety of judgement. Under the conditions of techno-fetishism and urbanism, he continues to pose uncomfortable questions about the price of technological development and its social and existential consequences. The book Tradition and Future Shock: Visions of a Future that Isn’t Ours is written from a distinctly Traditionalist standpoint, which inevitably makes it polemical, since Traditionalism contradicts the modern world and the techno-optimism, progressivism, and archeofuturism that dominate it. Similar ideas can be traced back to Julius Evola and other Traditionalists (Guénon, Schuon, Burckhardt, de Maistre), who saw the need for a true “cultural revolution” based on a critical, Traditionalist comprehension of science and technology.7 Following this tradition, the author proposes to critically reconsider science and consider various existential strategies of resistance, which are presented in the concluding part of the book.

If technologies become obsolete, then it is fair to presume that the same applies to reflections on specific technologies. This idea expressed in the introduction is true in general, but why is this always the case? And, above all, does it also apply to the author? I believe that just as obsolescence does not belong to the very nature of Heidegger or Jünger’s books on the same problem, so will Nechkasov’s book probably not require any upgrade over time. The author addresses the ontological nature of technology, which ensures the timeless value of the analysis he presents. Written in the pivotal period of 2017-2020, at the junction of the pre-COVID and COVID periods, the book demonstrates astounding prognostication. What seemed like mere conjecture in 2017 is today rapidly becoming part of people’s lives.

We have grown accustomed to the unswerving development of technology, but few are capable of accurately predicting even the near future. And this future, contrary to the utopian promises of techno-optimists, will greet us not with positive changes, but with a sterile world and faceless, mystery-less world in which man is increasingly estranged from active and deep life to the point of losing any possibility of authentically existing as Dasein. Instead of qualitative growth, the opposite tendency is observable: the greater the perfection of technology, the stronger it degrades man. Man’s existence is increasingly characterized by the paradoxical capacity of das Man to turn the unique into the ordinary. Das Man’s ability to “deface” is not even some kind of exterior action, but the inner, existential quality of modern man’s existence. “Thrownness” (Geworfenheit) in this state of being turns into the “falling” (Verfallen) of the integrity of perception. Man loses integrity, dissipates in the chaos of total ordinariness, and is soothed by scrolling feeds on social networks. More so than ever before, modern man’s Dasein exists in a state of constant falling, mixing, destroying, and degrading.

In the conditions of the rising existential crisis generated by man’s alienation from authentic Being through the medium of technologies, transhumanist ideas are gaining in attractiveness. They offer simple solutions for complex problems: a cheap exit from the existential impasse, an aspiration for concrete “immortality” within the already given material world, and liberation from the burden of freedom that already weighs heavily on so many people. The deeper a person dives into the technological world, the less space he has for genuine freedom. Man searches for ever new sources of pleasure amidst which he can forget himself, even if they cause him to suffer and destroy his own life.

This prospect is attractive to various intellectual circles which are thoroughly examined by the author of this book. Sciensters see progress as an end in itself and are passionate about popularizing the overall scientific picture of the world. Postmodernists, striving to deconstruct traditional notions of man, find in transhumanism an additional tool for blurring the boundaries of human identity. Cyberfeminists consider cyborgization to be a means for overcoming gender problems and getting beyond biological determination. The final sentence of Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto is memorable: “Though both are bound in the spiral dance, I would rather be a cyborg than a goddess.”8 In this phrase, the cyborg and the divine are linked, but behind the facade of mechanical dreams it becomes obvious that the future described by transhumanists does not belong to humans; moreover, it is devoid of divine presence. It is not our future; it is the future of posthumanism, which can only be described as total misery worthy of the brush of Zdzisław Beksiński.

Offenheit

“Heidegger has the notion of Offenheit (“openness”), and he writes in Sein und Zeit (Being and Time) that the world was once “open.” He contrast this “open” world to the “closed” world in which all of us live. This means that we can no longer simply go into the forest or take a stroll in the field. And here is the sense in which we cannot do this: we are closed people, we do not know the herbs that grow there, nor the birds that are singing. We are all distinguished by an aggressive, analytical psychology. Let’s say that a botanist explains something to us about a dandelion, something that we can read in any textbook, or says “and here there’s a robin singing, it’s spring now, the robin is celebrating a wedding.” We might even distinguish the robin’s song from that of a goldfinch, although this would be difficult. This is all that we can know about living nature, and yet it might give us an advantage over most of our companions. This is what the “closedness” of modern man towards nature means.”

— Evgeny Golovin, “John Dee and the End of the Magical World”9

“This time is destitute because it lacks the unconcealedness of the nature of pain, death, and love. This destitution is itself destitute.”

— Martin Heidegger, “What Are Poets For?”10

From man wielding a club to the office clerk representing the “crown of civilization,” devoid of gender, name, memory, thinking, and language — this is the sad path of “progress” visually represented on the book’s cover. This is truly the best illustration of the “disenchantment” of the world, and it extremely accurately corresponds to the content presented therein.

The massacre at Wounded Knee and the tragic finale of the Ghost Dance movement serve as a second striking example, as an image of the civilizational collapse of non-Western societies under the onslaught of Westernization. Given that the messianic Ghost Dance movement was founded in the late 19th century, it can be concluded that this faith arose out of the soil of modernist involvement in so-called reality, as a result of which the Indians suffered their decisive and final defeat that marked the collapse of their traditions and the triumph of Modernity in North America. “Dreams of gunpowder vanquished the shaky dream of the living dancing with the dead,”11 and thus an end was put to the magical, “enchanted” world of those lands.

The latter illustrates only one particular case of the implantation of the materialist picture of Modernity through colonial expansion, which reaches far wider than the West of the United States of America. Attempts at globalizing the values of Modernity, which include radical egalitarianism and technological determinism12, have encountered resistance on the part of non-Western societies which perceive them as neocolonialism.13 However, it bears noting that these societies have already significantly changed under the influence of Western logic.

Decolonial logic is undoubtedly dear to the author, and this is obvious from the book’s very first pages. But is it possible for there to be another, different traditionalism? This problematic lies an order of magnitude deeper than the sphere of external geopolitical confrontation; it lies in the metaphysical field of deep, paradigmatic shifts — it is a question not of time, but of eternity.

Following Alexander Dugin, Nechkasov analyzes the ontological foundations of reality. This corresponds to the approach presented by Dugin in his work Post-Philosophy: Three Paradigms in the History of Thought: “Reality is the term that started to define what we are dealing with exclusively in Modernity. Before this, there was no reality in pure form.”14 This is a wonderful and unjustly forgotten thought: manifestationism (i.e., Tradition itself) sees the world through the prism of the sacred, ignoring the material foundation of Being — the laws of physics, chemistry, biology. The world of manifestationism is diverse and permeated with sacred trembling. Any attempts to ontologically determine anything outside of the Absolute are met with objection: even the smallest thing can be a manifestation of the Absolute. This ontology was replaced by creationism and then by Modernity, which marked the break with sacred ontology, substituting it with a rational, secular paradigm of a world without God or Gods, a world without poetry. From Heidegger’s point of view, this history represents the degradation of the thinking of Being, which passes from nature to the will to power and mechanicism (Machenschaft).15

Wohnen

Ohne Verdienst, undichterisch

wohnt heute der Mensch,

entfremdet den Sternen,

verwüstend die Erde.

Dwelling

Mankind dwells unpoetic

today, without profit,

estranged from the stars

devastating the earth.16

Modernity is the result of the blatant de-sacralization of Being, where the place of God is taken by reason, and the place of Tradition yields to blind faith in progress. But the world of Modernity, founded on the objectivity of scientific knowledge, is no more than a myth. Bruno Latour, taking the example of the English physicists of Newton’s time, demonstrated that the scientific experiments presented to the royal family were meticulously planned with theatrical settings and magician-like sleights of hand performed by scientists intended to convince the king of the truth of the new scientific knowledge. The illusion of credibility and verifiability created by all sorts of “science shows” was inlaid as the cornerstone of the reputation of scientific laboratories.

From the primordial sacrality of the world to alienation in the technogenic world — such is the path traced in this book.

Let us compare two existential models. The first is the “savage” from the Amazon rainforest, the embodiment of Heideggerian Offenheit, openness to the world thrown to his encounter. He is part of the living cosmos, he understands the language of the forest, reads animal tracks like writing, and in every creek he feels the living pulsation of the earth. His world is sacred, filled with the living presence of the divine. The second is the modern clerk, walled up in a glass tower, a giant “ziggurat” like one of the buildings of Moscow-City. Like a minotaur, he wanders aimlessly through the concrete labyrinths where all the buildings are monstrously similar to one another. His motto is Homo homini lupus est. What do you think: whose existence is characterized by greater ontological depth?

The roar of the highway buries the whisper of the wind that holds ancient secrets now inaccessible to modern man, who has lost the ability to hear. The neon lights of the megapolis eclipse the stars, the sky is pierced by the cold bodies of artificial satellites. They entangle the world in a dense technological web, equipping man with everything which he can no longer exist without: signal connection, navigation, GPS, weather forecasts, maps, calculations, television, and radio.

What we need is that gift of imagining the possibility of prayer, indispensable to anyone in pursuit of his salvation. Hell is inconceivable prayer.

“Whoever cares about salvation must be convinced that prayer is possible; there is nowhere from which we might take this conviction. Hell is the inconceivability of prayer” — thus wrote Emil Cioran.17 Are we not in this hell today? Is this dead cosmos hell? Is hell not the extinguishing of the sun of the spirit?

Once upon a time, Heidegger noticed the rapid process of the world’s compression, one consequence of which is the disappearance of the usual scales of space and time. Travels once bound up with danger and stretching out for months are now completed overnight in comfortable liners. News that used to arrive with a delay of months or even years is now available in real time on our smartphone’s screen. Notions of “near” and “far” lose their meaning and merge into a homogeneous mass — the ideal habitat for Nietzsche’s last man who is tired of life and freedom and rejects any risk in the name of absolute comfort and safety.

Cites are increasingly similar to each other, differing only in the most superficial details (the assortment of elite coffees, the latest models of electric scooters, the selection of services and amenities), only in greater or lesser degree of technological perfection. Man imagines that he lives in an open world, but this world is no more than a glass cage with clearly demarcated boundaries. Man is constantly entertained so that he doesn’t feel his total lack of freedom. Taken together, all of this is the true “closed-offness” of the world, a world that has become a prison, a world where technological “progress” turns into the tragedy of “homelessness”. “The loss of autochthony springs from the spirit of the age into which all of us were born,” Heidegger says.18

What is important to bear in mind in the midst of this situation? What does the author urge us to think about? Technology is not neutral; it changes our ontology and our being in the world. We fall into slavery to technology precisely when we see something neutral in it. This now widespread illusion completely conceals its essence from us.19

The Forest

"The ship signifies being in time, the forest supra-temporal being. In our nihilistic period, an optical illusion grows whereby the moving appears to increase at the expense of the resting. In truth, all the technical power that we see presently unfolding is but a fleeting shimmer from the treasure chests of being. If a man succeeds in accessing them, even for one immeasurable instant, he will gain new security—the things of time will not only lose their threatening aspect but appear newly meaningful.”

— Ernst Jünger, The Forest Passage20

The third part of the book examines existential strategies for surviving in the conditions of the modern world and the exacerbated, aggressive interference of technology. Let us dwell in detail on one of these strategies: the forest passage proposed by Ernst Jünger.

Jünger uses the metaphor of a ship heading towards certain death to describe the position of modern man enslaved by technogenic civilization. The opposite of this Ship is the Forest, which is not a physical refuge, but rather a state of the spirit, the “vertical axis,” the space of inner independence.

Jünger is not propagating escapism. He is not calling for flight. Rather, he calls for active resistance to the aggressive technogenic environment. Lost in the world of technology, man loses his sovereignty and capacity for resistance. The forest passage is not a flight into nature and not a guerrilla war, but the deepest, innermost transformation of man — it means cultivating the “vertical axis” that is insubordinate to external illusions and mirages in the heart of technogenic reality, in the heart of hell.

In Tradition and Future Shock, Nechkasov follows Jünger in drawing an interesting parallel between modern humanity and the passengers of the Titanic who were blinded by the illusion of the perfection of technology and strolled carefree on the ship’s deck. They enjoyed imaginary freedom all the while as the ship to which they had entrusted their lives moved full speed ahead towards disaster. Having delegated their fate and will to machines, they became hostages of the myth of progress. The iceberg is the supreme extremity of the collapse of the illusion of technology’s omnipotence. Where will these people’s freedom and independence be when the Titanic sinks to the bottom? What will happen to those who are used to daily likes and constant encouragement on social media when they are suddenly left without it?

What will happen when gadgets become useless toys, and information becomes dust? Deprived of external data storage, consciousness will be forced to rely solely on its own memory and the traditional methods of preserving information. In the absence of external encouragement, people will have to painfully search for a solid basis of support within themselves. For most people, this will mean existential death, or becoming aware of the fact that they might never have truly lived. Dispelling these mirages means drawing closer to the truth. But is there another way? There is the individual path to the forest passage, which is achievable by overcoming the Ship.

In connection with this, the famous myth of Dionysus comes to mind, for overcoming the Ship is like the Dionysian transformations: Dionysus acts from within, changing the very essence of things. In the myth about the Tyrrhenian pirates who dare to take Dionysus hostage, the ship is miraculously transformed: Dionysus takes the form of a lion, the masts and oars are entwined with snakes, the ship is covered in ivy, and the air is filled with the sweetest sounds of a flute. The pirates, seized by madness, throw themselves into the sea and turn into dolphins.21

The forest passage means cultivating the inner “vertical axis,” sprouting up and beyond the Ship’s mast, dissolving the reality of Modernity in one’s heart — indeed, many religious and philosophical traditions define the heart as the “topos” of intellectual intuition.22 This axis is the backbone of authentic rebellion. The assertion of such sovereignty is the true meaning of Jünger’s metaphor and one of the paths of existential resistance.

The forest passage is death; it is the path to Dionysus as well as other forces that stand opposed to the world enslaved by technology, the world of the Titans. It is the path through death, but, just as a tree grows out of death, this path generates the possibility of resistance. Just as Heidegger spoke of springing from death, so in this case does death become the source of new life.

Saat

Ihr sucht Entstiegenes

in Traum und Not.

Sät erst Gediegenes

zum Baum aus Tod.

Sowing

You want what bursts

in crisis and dreams.

Sow the solid first

among death’s trees.23

Heidegger speaks of the possibility of transforming death into something else, of the possibility of rising up to a tree out of death, and in The Forest Passage Jünger underscores the possibility of overcoming the powers of the time by resisting fear of death, drawing inspiration from gods, heroes, and wisemen. By conquering this space of inner freedom, man gains the capacity to resist fear and to crush the giants whose power is based on horror. This is the supra-temporal principle of victory.

Victory is achievable by confronting horror, death, tragedy, and catastrophe, as well as through actively reflecting on the extreme experiences and truth of Being.

***

READ MORE: Tradition and Future Shock: Visions of a Future that Isn’t Ours (PRAV Publishing, 2023).

20% discount code for subscribers below: