Overcoming the West

Nikolai Trubetzkoy and the Legacy of Eurasianism

Overcoming the West

by

Alexander Dugin

Originally published in Russian as the foreword to Nikolai Trubetzkoy, Nasledie Chingiskhana [The Legacy of Genghis Khan] (Moscow: Agraf, 1999).

A Monument on “Eurasia Square”

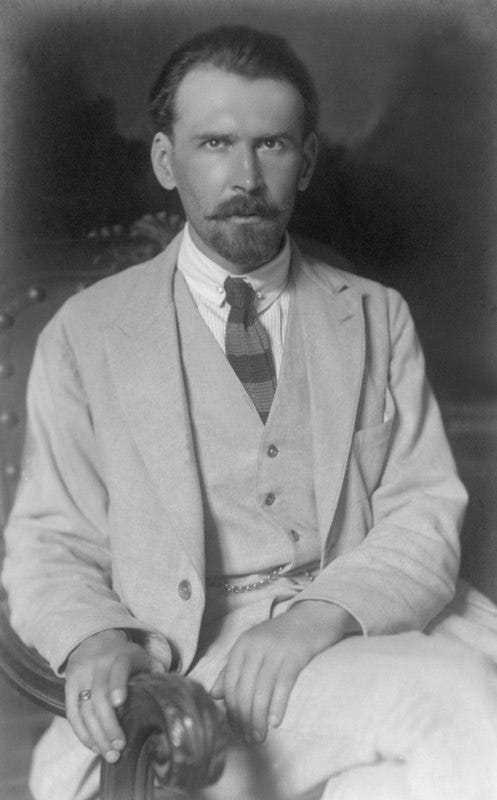

Prince Nikolai Sergeevich Trubetzkoy (1890-1938) may by all rights be called “Eurasianist Number One.” It is to none other than him that the basic premises of this incredible, creative worldview belong. Prince Trubezkoy could be called the “Eurasian Marx,” just as Petr Savitsky clearly evokes the idea of a “Eurasian Engels.” The first strictly Eurasianist text was a book written by Nikolai Trubetzkoy called Europe and Mankind, in which the fundamental principles of an emerging Eurasian ideology can easily be deduced.

In a certain sense, it was precisely Trubetzkoy who founded Eurasianism, who discovered the primary lines of force of this theory, which would later be elaborated by an entire pleiad of the most prominent Russian thinkers – from Petr Savitsky, Nikolai Alekseev, and Lev Karsavin to Lev Gumilev. The place of Trubetzkoy in the history of the Eurasian movement is a central one. Once this tendency is affirmed as the dominant ideology of Russian statehood (and this will inevitably happen, sooner or later), it will be to him – Prince Nikolai Sergeevich Trubetzkoy – that the first monument will be erected. His will be the main monument on the future great “Eurasia Square,” swimming as it shall be in luxuriant foliage and the purest streams of silver fountains.

The Fate of the “Russian Spengler”

To speak of Trubetzkoy is to speak of Eurasianism as such. His personal and intellectual fate is inseparable from this tradition. His biography is extremely simple: a typical representative of a most famous princely line, which had yielded a panoply of thinkers, philosophers, and theologian; he received a classical education, specializing in the field of linguistics. He took an interest in philology, Slavophilism, Russian history, and philosophy. And he distinguished himself with his brilliant patriotic fervor.

During the Russian Civil War, he came out in support of the White movement and emigrated to Europe. He spent the latter half of his life abroad. Beginning in 1923, he taught in the Slavic department of the University of Vienna, focusing on philology and the history of Slavic writing. Along with Roman Jakobson, Trubetzkoy belonged to the core founding group of the Prague Linguistic Circle, which developed the bases of structural linguistics – that intellectual movement which would later come to be known as “structuralism” – during the 1920s and 30s.

Prince Nikolay Trubetzkoy was the soul of the Eurasianist movement, its main theorist, and a Russian Spengler of a sort. One should begin the history of this movement with the publication of his book Europe and Mankind.

Selected excerpts from Trubetzkoy’s Europe and Mankind, prefaced with a critical essay by the contemporary Eurasianist Leonid Savin, can be read in Foundations of Eurasianism — Volume I (PRAV Publishing, 2020). An extensive introduction to Trubetzkoy’s life, works, and role in the Eurasianist movement, penned by scholar Ksenya Ermishina, can be found in Foundations of Eurasianism — Volume II (PRAV Publishing, 2022).

It was Trubetzkoy more than anyone else who actively developed the principal aspects of Eurasianism. But, being a scholar who devoted a significant amount of time to his philological studies, he scarcely and only begrudgingly took an interest in the application of his theory to the politics of the day. His close friend and comrade Petr Savitsky would fulfill the role of political leader within the movement. Trubetzkoy’s temperament was more disinterested, characterized by a penchant for intellectual speculations and abstraction.

The crisis of politics in Eurasianism, which became apparent at the end of the 1920s, bore a heavy, painful toll on its main theoretician. With the consolidation of Soviet power in Russia, the contingency, archaism, and irresponsible attitude of the Russian emigration, and the spiritual and intellectual stagnation which took hold in both branches of Russian society in the 1930s following the spiritual cataclysm at the start of the century, Eurasianist ideology, founded on a plethora of the subtlest intuitions, paradoxical epiphanies, and passionate flights of political imagination, had come to a dead end. Seeing how Eurasianist ideas were being marginalized, Trubetzkoy dedicated his last years all the more to pure scholarship: he stopped participating in the polemics and conflicts within the movement after its schism, and he turned a blind eye to the criticisms of Eurasianism coming from its enemies in the Russian emigration — undoubtedly the product of ressentiment. In 1937, in Vienna, Prince Trubetzkoy was captured by the Gestapo and spent three days in jail. During this time, the aged scholar suffered a stroke from which he never recovered and died soon after.

His death went practically unnoticed. A terrible catastrophe came over the world. Its main ideological tenets were a rejection of those principles and axioms which the Russian Eurasianists and their European analogues – the proponents of Conservative Revolution, National-Bolshevism, and the Third Way – had managed to formulate on the highest level of spirit and with the greatest intellectual effort.

The Eurasianists foretold with prophetic foresight the paths which future worldviews would take and the politics that would result therefrom. But, alas, the fate of prophets has been the same in every age: stoning at the hands of a mob, burning at the stake, expiration in the GULAG, or fatal imprisonment at the hands of the Gestapo…

Humanity Against Europe

The most valuable aspect of Prince Trubetzkoy’s thought, and the fundament of the entire Eurasianist worldview, is his affirmation of a radical dualism of civilizations, his interpretation of the historical process as a contest between two alternative projects. It is to this dualism that he devotes his first theoretical work, Europe and Mankind. There, in paltry and often imprecise terms, he expresses the following idea: there is no single path of civilizational development; such a pretension can only mask the strivings of a particular, concrete, and aggressive form of civilization, namely the Romano-Germanic world, toward universality, singularity, hegemony, and absoluteness.

It is because of the megalomaniacal and essentially racist pretensions of the Romano-Germanics to become the common measure of culture and progress that one must divide the world into Europe on one side and Humanity on the other. The Romano-Germanic world, being no more than one part of a multipolar, many-cultured historical reality, took on the Satanic pretension of being a conceptual whole, haughtily relegating other cultural types to the territory of barbarism, underdevelopment, and primitivity.

Mankind, in Trubetzkoy’s understanding, serves as a category uniting all peoples, cultures, and civilizations which stand apart from the European model. Trubetzkoy argues that this distinction is not just a disputation of facts, but a formula of civilizational, historical opposition – a demarcating line along which modern history has proceeded. The Romano-Germanic world is not bad in itself, according to Trubetzkoy; in fact, in its capacity as only one among many worlds, it would be extremely of interest and substantial. What is unacceptable and inadmissible in it is its aggressive attitude toward all other cultures, its colonialism, domination, inclination toward civilizational genocide, and enslavement of everything that is “other” in relation to it.

For this reason, Trubetzkoy writes, Mankind must come to recognize its unity by negating the totalitarian model of the modern West, bringing together the “flowering complexity” of peoples and cultures into a single camp in an anti-Western, liberational, planetary battle.

Trubetzkoy saw Eurasia as the most generalized form of Mankind, of its “flowering complexity” (a term coined by Konstantin Leontiev). Eurasia was the ideal formula used to describe how the steppe Turanians of Genghis Khan had passed along their spirit to Muscovian Rus’. Within such a picture of the world, Russia-Eurasia became the bulwark and lever of Mankind’s planetary battle against the universal Romano-Germanic yoke.

It is surprising just how consonant this thesis was with the position of the founder of Traditionalism, René Guénon, who in his book East and West makes an almost identical argument, with the exception of the idea that Russia would be the one to play a particular role in the planetary opposition against the modern West. It is difficult to say whether Trubetzkoy was acquainted with Guénon’s writings. All we know is that Guénon is mentioned in the texts of another prominent Eurasianist and collaborator of Trubetzkoy’s: Nikolai Nikolaevich Alekseev. But if in Guénon’s work one reads only of the need for the camp of remaining traditional societies to resist the modern West, then the Eurasian project (besides its fully justified pessimism with regard to the inertial development of historical events) contains a developed futurological and revolutionary component, by which it strives to propose a new sociocultural form which would combine fidelity to tradition with socio-technological modernism.

The chief hope of Trubetzkoy and all Eurasianists was Russia – the motherland for which they harbored a burning love. It is precisely in Russia that they saw the paradoxical combination of two principles: an archaic rootedness in Tradition and an avant-garde thrust in the direction of cultural and technological development. In Eurasian ideology, Russia-Eurasia was thought to be the vanguard of Mankind in its opposition to Romano-Germanic Europe, as a frontline territory in which the fate of the rear would be decided.

Out of this general approach, concretizing as it did the various aspects of the initial paradigm, the theory of Eurasianism manifested real content. Whatever details their concrete investigations might have yielded, the primordial civilizational dualism revealed and postulated by Prince Trubetzkoy ever remained the common denominator, the unchanging background of the entire Eurasian discourse – both in its orthodox form, realized along the lines of Savitsky, Alekseev, and Suvchinsky, and in its heretical Marxist-Fedorovian form followed by the Eurasianists in Paris, undoubtedly Sovietophiles (Efron, Karsavin, etc.).

The Eurasian Paradigm of Rus’

Trubetzkoy’s general position determined the specificity of the Eurasianists’ views on Russian history. The Eurasianist thinker to have given the most intricate expression to this discourse was Georgy Vernadsky, son of the great Russian theorist of the “noosphere.” In his numerous works, he developed the Eurasianist panorama of Rus’.

Two of Georgy Vernadsky’s seminal essays on medieval Russian history, “The Two Heroic Feats of St. Alexander Nevsky” and “The Mongol Yoke in Russian History”, are presented in Foundations of Eurasianism — Volume III (PRAV Publishing, 2024):

But even this monumental exposition is in essence no more than an extension of the theses formulated by Prince Trubetzkoy. The dominant feature in the Eurasianist understanding of Russian history is the notion that the essence of the Russian people and the Russian state is something radically different from that of the Romano-Germanic world. In this understanding, Rus’ is thought of as an organic part of Mankind in its stand against Europe. Consequently, one must carry out a total revision of the Russian historical school, which had previously taken the canons of European scholarship on the matter, either directly or indirectly, as its point of departure. Naturally, Slavophiles such as Dostoevsky, Leontiev, and Danilevsky had made great strides in offering an alternative, strictly Russian (and not Romano-Germanic) evaluation of our historical path. The Eurasianists saw themselves as continuing this Slavophilic tradition. However, they were even more radical and revolutionary than their forebears when it came to the question of overcoming the West. They insisted not only on emphasizing our national specificity, but also on the alternative natures of civilizational paradigms, such as that of Europe and that of the organic, bedrock essence of Rus’, or Rus’-Eurasia.

All eras during which Russia drew close to the West were seen by the Eurasianists as anomalous. On the other hand, all Russian appeals to the East – to Asia – were interpreted by them as steps toward spiritual self-affirmation. Such a radical view overturned all the norms of our domestic historiography and historiosophy. If the Russian Westernizers, given their contempt for our Motherland, thought of Rus’ as a backward, “not-quite-European” country, then the Slavophiles, almost by way of self-justification, attempted to defend our national specificity. The Eurasianists went much further than this, not stopping at a mere defensive apology of Russian specificity. They affirmed that the Romano-Germanic world, along with its culture, is a historical pathology, a dead-end cul de sac of degeneration and fallenness. The ideas of Trubetzkoy resonate to a significant extent with the conceptions of the German Conservative Revolutionary Oswald Spengler, who posed a similar diagnosis of the West and prophesied a future salvific mission for the Eastern regions of the Eurasian continent.

The general picture of the Eurasianist view of the history of Rus’ is laid out in Prince Trubetzkoy’s programmatic text, The Legacy of Genghis Khan.

For Trubetzkoy, the 200-year-long period of Muscovian Rus’ which followed Tatar-Mongol domination and preceded the Petrine period was the axis of Rus’ as such, the central, paradigmatic moment of its history, when the ideal and the real were superimposed upon each other. Kievan Rus’, to which historians have traditionally ascribed the sources of Russian statehood, cannot be seen civilizationally, culturally, or geopolitically as the cradle of Rus’, according to Trubetzkoy; rather, Kievan Rus’ was no more than one of several components of the emerging Russian Tsardom. Overwhelmingly Slavic, occupying the territories between the Baltic and Black Seas, rooted in forested zones and on local riverbanks, weakly controlling the area of the steppe, Kievan Rus’ was merely a variation of the Eastern European principality model, the centralization of which was later greatly increased, and which generally always lacked an integral idea of itself. Kievan Rus’ was only a religious province of Byzantium and, politically, a province of Europe.

The Tatar-Mongol invasion made easy work of this half-baked geopolitical construction, absorbing it as a component part. But the Mongols were no mere barbarians. They fulfilled a great empire-building function, laying the foundation for a gigantic, continental state, the base of a multipolar Eurasian civilization which would serve in essence as an alternative to the Romano-Germanic model while remaining fully capable of dynamic development and cultural competition.

In various ways, Trubetzkoy emphasizes the colossal value of the Turkic-Mongolic impulse, insightfully drawing attention to that most important geopolitical fact that all of the spaces of eastern Eurasia have been integrated thanks to the unification of the steppe which stretches from Manchuria to Transylvania. The Tatars completed that which was first outlined by geography and, in so doing, became a fact of planetary history.

In Trubetzkoy’s estimation, the authentically Russian, Eurasian state emerged at the moment when the Muscovian princes took upon themselves the geopolitical mission of the Tatars. Muscovian Byzantinism became the dominant state ideology only after the fall of Byzantium, and in organic confluence with a governmental structure taken wholesale from the Mongols. Herein lies the essence of Holy Muscovian Rus’, imperial and Eurasian, continental, strictly distinct from the Romano-Germanic world and radically opposed thereto.

The two hundred years of Muscovian Rus’ were two hundred years of Rus’ in its ideal, archetypal state, in total conformity with its own cultural-historical, political, metaphysical, and religious mission. And it was precisely the Great Russians, having spiritually and ethnically mingled with the Eurasian empire-builders of Genghis Khan, who became the nucleus and seed of a continental Russia-Eurasia and fused culturally and spiritually into a singular, integral, state-forming ethnos.

This is a point of extreme importance: the Eurasianists emphasized the exceptionality of the Great Russians amongst all the other Slavic tribes. Being Slavs racially and linguistically, the Great Russians were the only ones among them who were Eurasian and Turanian in spirit. It is here that we may discern the unique quality of Moscow.

Having seized the initiative of the original impulse of Genghis Khan, the Muscovy Tsars undertook to restore the Tatar-Mongol Eurasian State, unifying its fragmented segments into a new empire under the aegis of the white Tsar. This time, the cementing religion became Orthodoxy, and the state doctrine became the Muscovian version of Byzantinism – famously evoked by the monk Filofei in his dictum that “Moscow is the Third Rome.” The practical organization of the government and, most importantly, the vector of its geo-spatial formation was a calque of the empire of the Tatars.

The end of the “ideal Rus’” coincides with the end of “Holy Rus’” in the form of the schism. The reforms of Patriarch Nikon, formally directed at fortifying the geopolitical might of the Muscovian Tsardom but implemented by means of a criminal culture and religious negligence and sloth, led to ambiguous and, in many senses, catastrophic results which cleared the way for the secularization and Europeanization of Russia.

The schism was the point of rupture between secular Russia and Holy Rus’.

With the arrival of Peter I, we observe the beginning of what in Eurasianist theory is referred to as the “Romano-Germanic yoke.” If the “Tatar yoke” was for Russians the ferment of an emergent era of empire-building and the Eurasian impulse, then the “Romano-Germanic yoke,” spanning from Peter the Great to the October Revolution of 1917, brought only alienation, a caricature and degeneration of the previous, profound impulse. Instead of asserting Russian cultural specificity and the Eurasian Idea, those under the sway of the Romano-Germanic model put forth an awkward imitation of the European aristocracies, along with their universalist and rationalist blueprints for a secularized society. Instead of Byzantinism, we got Anglicanism. Instead of “flowering complexity” (Konstantin Leontiev), we got a grey bureaucracy and sterile military servility. Instead of living faith, we got a clerical synod. Instead of folk spontaneity, we got the cynical chatter of official propaganda, veiling the total cultural alienation of the Europeanized elite from the archaic lower layers of society.

The Eurasianists saw the Romanov period, beginning with Peter I, as essentially a rejection of the Muscovian stage, accompanied by a cosmetic parody thereof. The Romanovs would continue to assimilate the East of Eurasia, but, instead of undergoing an organic process of affiliation with the peoples of this area, they would impose a “cultural assimilation” in conformity with the Romano-Germanic model. Instead of facilitating a rich dialogue of civilizations, they imposed a formal Russification. Instead of allowing for a common expression of continental will, they applied the flat methods of Western colonialism.

Here, the Eurasianists, like the Slavophiles and the Narodniks, divided the history of post-Petrine Russia into two categories: that of the aristocracy, and that of the people. The elites went the way of Westernization, aping with a greater or lesser extent of awkwardness the European model. They acted as a sort of “colonial administration” in Russian lands, as civilized overseers of the “barbarous people.”

Meanwhile, the lower layers of society – that very “barbarous people” – remained totally loyal to the pre-Petrine order while carefully preserving elements of the holy times of old. It was precisely these autochthonic tendencies, which despite all odds still managed to have an effect on the elites, that constituted everything valuable, national, spiritual, self-generated, and Eurasian in Petrine Russia. If Russia avoided becoming a mere eastern annex of Europe in spite of the “Romano-Germanic yoke,” then it is only thanks to the essence of the people, the “Eurasian dregs,” who carefully and passively, but insistently and unflinchingly, resisted the penetration of Europeanizing impulses.

From the perspective of the elites, the Petrine period was catastrophic for Russia. But this was partially compensated by the general “ensoiled” attitude of the Eurasian masses.

This model of Russian history elucidated by Trubetzkoy would also condition the Eurasianists’ attitude to the Revolution.

Revolution: National or Anti-National?

The Eurasianist analysis of the Bolshevik Revolution served as an axial event in their worldview. The particularity of their analysis distinguished them from all other camps.

There were two broadly acceptable views of the Revolution among partisans of the White movement: reactionary monarchism or liberal democracy. Both factions viewed Bolshevism as an exclusively negative phenomenon, even if they did so on diametrically opposed bases.

The reactionary monarchist wing insisted that “Bolshevism” was an entirely Western phenomenon, a result of “conspiracy” between the European powers and racial aliens within the Russian empire (non-Russians and, specifically, Jews), aimed at the destruction of the last Christian Imperium. This group idealized the Romanovs, seriously believed in the formula of Count Sergei Uvarov which held that the basis of Russian statehood was “Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Narodnost’,” subscribed to the “myths of the Black Hundreds” about the “Judeo-Masonic World Government,” and blamed the weakness of the pre-revolutionary authorities – their insufficient punitive apparatus and the betrayal of the intelligentsia – for everything. They viewed the Revolution as an infection contracted from without, the development of which was helped along by incidental and hostile elements that were foreign to the Russian system. By contrast, pre-revolutionary Russia herself, with all her ideological and social underpinnings, was held up by this camp as something absolute.

The liberal wing of the White emigration saw Bolshevism as an absolute evil for entirely antipodal reasons. They discerned in Bolshevism the manifestation of a barbarism inherent to the Russian masses, who were incapable of accepting the enlightened, democratic “February Revolution,” and who perverted its liberal reforms into “tumult, wildness, and the marauding of unconscious, unenlightened impulses.” The liberals critiqued the Bolsheviks not for the elements of Westernism in their ideology, but for the dearth thereof – not for their external forms, but for their popular content.

Both of these positions among the Russian emigration perpetuated the debate between the two camps into which the ruling elite of the Romano-Germanic type had been divided during the last century of the Russian Empire. This debate was framed by one and the same “colonial administration,” equal parts anti-popular and abstracted from the Eurasian identity of Rus’. The reactionaries were of the view that the Eurasian masses ought to be bound in a tight harness, that they would not be receptive to “acculturation.” By contrast, the liberal Westernizers believed that, given certain specific circumstances, those masses could eventually be fitted out on the model of European societies.

For their part, the Eurasianists proposed a completely unique interpretation of Bolshevism, one which flowed from entirely different suppositions. They suggested that the historical reflexivity of the ruling class under the tsarist system had been generally inadequate and lacking in national orientation. As a result, it had proved erroneous, criminal, and ultimately drove the unconscious impulses of the people to the point of radical revolt.

The Eurasianists saw the essence of Bolshevism in the ascent of the people’s spirit, in the expression of the deep bedrock of Rus’ that had been driven into the underground after the schism and remained there since the times of Peter the Great. They affirmed the profoundly national character of the Revolution, interpreting it as a chaotic, unconscious, and blind, but desperate and radical striving by Russians to return to the times preceding the “Romano-Germanic yoke.” The transfer of the capital from Petrograd (Saint Petersburg) to Moscow was seen by the Eurasianists as a manifestation of the same desire. In this sense, they were in agreement with the liberals about the national character of Bolshevism, but viewed this factor in a positive light, as Bolshevism’s most valuable, creative, and organic component.

On the other hand, the Eurasianists were traditionalists, Orthodox Christians, and patriots, oriented toward a national system of cultural values. For this reason, the Marxist terminology of the Bolsheviks was foreign to them. In this sense, they were more in line with the rightist circles of the Russian emigration, being of the opinion that the Westernizing, pro-European element in Bolshevism constituted its negative side and impeded the Bolshevist movement’s organic development in the direction of a robust Russian, Eurasian reality. Even so, the Eurasianists did not lay the blame for this negative, Westernizing component of the Revolution at the feet of a mythical “Judeo-Masonic” conspiracy, but rather of the Petrine model of governance, which was Westernizing in every respect and had so influenced Russian society in this regard that even a protest against the “Romano-Germanic yoke” could only be formulated in terms derived from the arsenal of European thought – more concretely, from the philosophy of Marxism.

Therefore, Trubetzkoy and his followers rejected the positions of both the reactionaries and the liberals, and they asserted an entirely unique and unusual trend in the intellectual ferment of the Russian emigration, one which captivated its best minds during the 1920s.

READ MORE:

The Eurasianist understanding of the Revolution was oriented both from the right and from the left. On the left, its proponents were extreme populists – a fraction of the Social Revolutionaries and the anarchists – who, unlike the liberal-democrats, took an exceedingly positive view of the popular, autochthonous element in Bolshevism. On the right were the conservative circles who had descended from the Slavophiles, namely Danilevsky and Leontiev, in whose eyes the Romanov regime represented its own kind of “liberal compromise.” The Russian National-Bolsheviks (Ustrialov, Kliuchnikov, et al.) adhered almost precisely to the same position as that of Prince Nikolai Trubetzkoy.

Of course, the Bolsheviks themselves expressed their understanding of Russian history in a slightly different manner. Their thinking was dominated in all respects by a narrow Marxist dogma, unsuited to the task of grasping and adequately comprehending multidimensional, cultural-civilizational processes and foreign to the history of religions and geopolitics. But, for the sake of fairness, it should be acknowledged that even the Bolsheviks (especially during their earlier stages of ideological development) had a tendency of likening Marxism to the heterodox religious doctrines of the people. In particular, with the blessing of the leaders of the Russian Social-Democratic Workers’ Party (RSDRP), Lenin’s closest collaborator Vladimir Bonch-Bruevich published a periodical titled New Dawn [Novaia zaria] for Russian sectarians and the most extreme of Old Believers.

The Eurasianists understood Bolshevism much more broadly, in the context of numerous factors within Russian history, taking into account the history of religion, sociology, ethnology, and linguistics. It is no coincidence that some of their detractors referred to them as the “Orthodox Bolsheviks.” Of course, this was something of an exaggeration against which Trubetzkoy himself protested, but there was nonetheless a seed of truth in the accusation, provided one is able to abstain from the pejorative meaning of the term “Bolshevism.”

For the reactionaries, the internationalism preached by the Bolsheviks was an affirmation of the anti-Russian, anti-national essence of their entire movement. The Eurasianists saw things differently. What they had discerned in the “proletarian internationalism” of the leaders of the Russian Revolution was not a drive to “annihilate the nation,” but to recreate, within the framework of the USSR, a singular Eurasian type, a mosaic of the “pan-Eurasian nationalism” about which Trubetzkoy had written.

Trubetzkoy’s essays “On True and False Nationalism” and “Pan-Eurasian Nationalism” are available in Foundations of Eurasianism — Volume I:

When viewed from this angle, Bolshevist internationalism, limited to the territory of the Soviet State and concerning primarily the plethora of Eurasian ethnoi, was for the Eurasianists only a euphemism for “imperial nationalism,” a special model uniting the continental peoples of the East, and for “Mankind” which, as Trubetzkoy understood it, was fundamentally opposed to “Europe.”

The Eurasianists’ ideal was not a matter of blindly copying the European “nationalisms” born from the common Romano-Germanic matrix, but instead of appealing to the Eurasian model of Muscovian Rus’, the commonality of which was ensured largely by a unity of cultural and religious type rather than by racial or linguistic kinship. Accordingly, they recognized in the practical national politics of the Soviets a familiar integral principle that was close to their own thinking. And, for this reason, they were also able to discern the Bolsheviks’ call for global decolonization, for the peoples of the East to shrug off the Romano-Germanic yoke, and for a movement of planetary liberation on national bases. To conduct such a politics was, in the eyes of the Eurasianists, to continue the Russian mission of planetary liberation.

On the Threshold of the Old Faith

In the religious sphere, Eurasianist theory inevitably leads to an affirmation of the idea that the authentic Orthodoxy which inherited the unbroken tradition of Muscovian Rus’ was that practiced by the Russian Old Believers, the Ancient Orthodox Church. In the same measure with which the anti-national Romanov dynasty led Russia into the catastrophe of the 20th century, the reforms of Patriarch Nikon – yielding as they did a servile, lifeless, synodic, and bureaucratic “orthodoxy” – led the Russians into atheism and sectarianism, having exsanguinated the true Faith and cast the people into the arms of agnosticism, banal materialism, and heresy. The Westernizing essence of the pseudo-monarchic, post-Petrine State found a most precise reflection in Nikon’s synodal “orthodoxy.” The Europeanized, Westernized elites of the Empire had transformed the official Church into something like a governmental department. This could not fail to express itself in the very nature of the Russian Church. The authentic Orthodox spirit had withdrawn into the people, the dregs, the schism.

It was only logical for the Eurasianists to make their appeal to the Old Believers, as the bearers of authentic Russian Orthodoxy. And so it was: Trubetzkoy (along with other Eurasianists and, in general, the best political and religious figures of his time, such as Bishop Andrei Ukhtomsky) fully recognized the rectitude of Archpriest Avvakum, the traditional status of the two-fingered sign of the Cross, the lawlessness of the “bandits’ council of 1666,” Patriarch Nikon’s reforms, and the unjustified and erroneous transition to the Little Russian canon of the Saints and theological texts from the previous Great Russian, Muscovian canon. But it is possible that the “lordly,” aristocratic origins of the leaders of classical Eurasianism prevented them from unequivocally and totally recognizing not only the historical, but also the ecclesiological legitimacy of the Old Believers. The aristocracy viewed the Old Believers as practicing the “religion of the rabble.” The elitists among the Russian intellectual class (which included the Eurasianists) experienced a preconditioned, class-based hesitance towards the “simple folk faith.”

Practically all of the Eurasianists were immensely interested in the Old Believers. Indicative of this is the cult of Archpriest Avvakum, whom the Eurasians considered the founder of all of Russian literature and whose Life they hailed as the first and most unique model of Russian national existentialism.

Ideocracy, or “Anagogic Totalitarianism”

The conception of an ideocratic state – an ideocracy – plays an important role in Eurasianist philosophy. At its foundation lies an understanding of the state and of society as a reality called up to realize an important spiritual and historical mission. This theory was given the name “ideocracy,” the “power of ideas,” and the “power of the ideal.” Such an approach stemmed from the Eurasianists’ more general understanding of human existence, the supreme predestination of the collective, the people, and all things held in common. The Eurasianists appraised the human fact to be a transitional stage, as a point of departure for self-overcoming; consequently, the entire anthropological problem was seen not as a given, but as a problem to be solved.

In its most basic features, this understanding is proper to all spiritual and religious traditions. Within modern philosophy, and in an entirely different context, we encounter an analogous perspective with Nietzsche and in Marx. The Orthodox Eurasianists could by all means follow Nietzsche in repeating his iconic maxim: “Man is that which must be overcome.” And this was fully in the spirit of Russian philosophy’s common aspiration to speak not about the lone individual, but about a general collective whole, to transfer the problematics of the anthropological situation onto the collective, which the Eurasianists, following Trubetzkoy, deduced from the imperative of all-encompassing self-overcoming. Raised to the level of a social and governmental norm, ideocracy was supposed to be the embodiment of this collective self-overcoming, self-ascending, self-transformation, and self-purification needed in order to carry out the supreme mission. The Italian Traditionalist philosopher Julius Evola referred to an analogous model of sociopolitical organization as “anagogic totalitarianism,” i.e., an order under which the being of each distinct person would be compelled to contribute to the spiral motion of a common spiritual ascending, ennobling, and sacralizing.

Trubetzkoy was of the view that the problem of ideocracy – its recognition or rejection – was not a matter of personal choice. Rather, it was the generally obligatory imperative of the historical collective which, by the fact of its own existence, was duty-bound to fulfill a complex task handed down to it by pre-eternal Providence. The most important thing in ideocracy is the necessity of founding social and governmental institutes upon idealistic principles, of privileging ethics and aesthetics over pragmatism and considerations for technical efficacy, of affirming heroic ideals at the expense of comfort, the accumulation of wealth, and security, and of legitimizing the supremacy of the heroic type over the mercantile type (in the terminology of Werner Sombart).

The Eurasianists identified the defining features of ideocracy in such phenomena as the various European fascisms and Soviet Bolshevism. However paradoxical it may have been, the totalitarian character of these regimes was seen by the Eurasianists much more as a good than as an evil. The only thing which they questioned in these historical forms (which radically differentiated them from communists and fascists) was their anagogic character. In these historical movements, the sacral, spiritual ideal had been replaced either by vulgar economism or by irresponsible and futile theories of race. Any authentic ideocracy suitable for Eurasia, in Trubetzkoy’s opinion, would need to incorporate a neo-Byzantine, neo-imperial model, enlightened by the salvific rays of true Christianity, which is to say Orthodoxy. Only this could ensure a sacral investiture for the totalitarian regimes, a sacramental blessing from the City of Invisible Light. But this Orthodox, Eurasian ideocracy did not imply confessional exclusivism, missionary aggression, or forced Christianization. The Eurasians thought of the future Orthodox ideocracy as the axis and pole of a planetary-wide uprising of various cultures, peoples, and traditions against the unidimensional hegemony of the utilitarian, bourgeois, colonial, imperialist West. In this light, one could propose an entire ensemble of ideocratic societies and cultures rooted in the history of various states and peoples. The sole unifying principle need only be the rejection of the Western anti-ideocratic formula and an understanding of the supreme, ideal task of each human group, understood as a singular whole, captivated by the passionate impulse of fulfilling its spiritual mission.

Alas, the hoped-for transformation of Bolshevism into an ideocracy along Eurasianist lines did not come to pass; instead, the most alarming forecasts of the Eurasianists with regard to the incomplete and self-contradictory Bolshevik ideocracy and its lack of appeal to supreme spiritual values were realized, damning the Soviet state to degradation, downfall, and deformation into that pragmatic, utilitarian, lifeless, and bourgeois order which had long before fortified itself in the Romano-Germanic West.

Sill, the high ideals of ideocracy – the Eurasianist conceptions of “anagogic totalitarianism” – remain surprisingly relevant today, granting meaning and an aim to those who struggle in their refusal to perceive Man and Mankind as a mechanical conglomerate of egoistic machines of consumption and enjoyment, and who believe that each of us, and all of us taken together, possess a supreme task, a spiritual content, and an ideal destiny.

Eurasianism and Structuralism

Today, whenever someone speaks of the philosophy of structuralism, this person generally neglects the fact that one of the founders of this method, which has left such a meaningful impression on all of modern thought, was Prince Nikolai Sergeevich Trubetzkoy, whose philological ideas became the fundament of the “functional linguistics” of the so-called “Prague School” which, along with the Copenhagen and American schools, is one of the three pillars of structuralist philosophy. Those who analyze the philological ideas of Trubetzkoy and his principal work, Foundations of Phonology (1938), draw no connections between them and their author’s Eurasianist worldview; the latter remains behind the curtains in the majority of scholarly studies of Trubetzkoy the linguist. On the other hand, historians of Eurasianism have paid little attention to Trubetzkoy’s linguistic research, considering this to be no more than a private fascination of his, utterly partitioned from his ideological activities. However, this is inaccurate. Philology and philosophy are most intimately interconnected, as the most penetrating modern philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche, made clear in his work We Philologists.

As affirmed in the famous hypothesis of the American structuralists Benjamin Whorf and Edward Sapir, “The language we speak shackles our perception of reality.” Language is the ideal paradigm of reality, preceding material things, predetermining and organizing materiality. Characteristic of structural linguistics as a whole is the drive to liberate oneself from the progressive, evolutive, rationalistic interpretation of language – from a language only identified with the logical causality of atomistic words. Instead, one must see language “holistically,” in its entirety, as a general, functional proto-structure which, in its most fundamental features, predetermines the words and messages arising from the common context, and not the other way around, i.e., not as being a composition of ready-made rational elements.

The school of the anthropologist and psychologist Gregory Bateson (1904-1980), following the above line of thinking, uncovered the so-called “analogical layer” of language, consisting of “sounds,” intonations, verbal errors, and the functional background which precedes the rational discourse constructed according to the laws of Aristotelian logic. Prince Trubetzkoy worked precisely within this current, which bore an ideal harmony with Eurasianism’s basic drive to overcome one-dimensional Romano-Germanic rationalism, and to transcend the bounds of formal logic.

It is telling that the structuralist method, in its overall contours, boils down to prioritizing the spatial paradigm. This is the so-called synchronic method, which is opposite to the diachronic approach. Such a choice of methodological priority in the sphere of linguistic analysis (or, more broadly, gnoseological and philosophical) is in fact nothing less than a projection of the basic idea of Eurasianism: the idea of a plural, multipolar, parallel, and multifarious development of national cultures in a “flowering complexity.” The Eurasianists opposed pluralistic humanity to the one-dimensional universalism of Europe, and it was precisely on the basis of that civilizational, geopolitical dualism that they situated the rest of their theories. Within the framework of linguistics, unitarian, classically “Romano-Germanic” logic corresponds to the diachronic approach, or the notion that the word-concept and logical construction are the essential foundations of language. The synchronic approach, on the contrary, allows for the derivation of parts from the whole, whereby the latter is grasped as a single, living organism, instead of as a dead, mechanical construction entirely predetermined by the functioning of its parts.

The “functional linguistics” of the Prague Linguistic Circle, of which Prince Trubetzkoy was an active member, therefore reveals itself to be a sort of projection of the spatial paradigm which characterizes the essence of the Eurasianist worldview into the sphere of linguistic science. The synchronic method inlaid at the foundation of structuralism is at once a movement of thought (reproduced on a different level and applicable to other realities) and the basic disposition of Eurasian philosophy.

By developing this realization and continuing our investigation of the correspondences between various scholarly disciplines and precepts held by various worldviews, we could very well arrive at an entirely new and unforeseen interpretation of the basic tendencies of modern philosophy, wherein a hidden matrix of profound dialogue between two latent proto-ideologies would shine through a veil of the most complicated terminological accretions. Such proto-ideologies will have been found to have determined entire trajectories of the various scientific and philosophical schools, beginning from their original impulse. But if a similar device used by Marxists has consisted in explaining the class character of one or another philosophy or scholar (which has occasionally led to exceedingly brilliant and productive gnoseological classifications), then in the current instance we would find ourselves faced with a different duality": the secret, unending battle between the gnoseology of Europe and that of Mankind – between the thought of the Atlanticists and the Eurasianists. And figures such as Prince Trubetzkoy would serve for us as the most important points into which an abstract politico-ideological worldview and the professional occupation of concrete scholarly investigation would be concentrated.

How many unexpected and revelatory correspondences would evince themselves in the event that we should juxtapose the history of modern structuralism with the basic tenets of Eurasianism? But that is another matter…

Eurasianism as a Project

The doctrine of the Eurasianists was extremely relevant at the time of the 1920s- 30s. It was filled with practically clairvoyant intuitions, revelations, and epiphanies concerning the mystery of Russia’s fate, as well as that of the world. The Eurasianists provided the most exhaustive and convincing analysis of Russia’s state cataclysms in the 20th century. They were able to rise above the clichés which defined their class and estate origins by accepting and intuiting the positive historical value of Bolshevism. But they remained true to the authentic roots of their own national and religious identity. They were motivated not by conformity, but by a valorous and brave striving to attain truth as it is, beyond the narrow and irresponsible banalities with which other worldviews have satisfied themselves.

Eurasianism took into itself all of the most brilliant and vivacious ideas of Russian politics belonging to the first half of the 20th century. But their ideas were not fated to attain practical realization. Their passionate, heroic leap found support neither in Soviet Russia, nor in the Russian emigration. No one paid heed to their prophesies, and events took their fatal course, drawing the world ever nearer to a catastrophe in which not only Russia or Eurasia, but Mankind as a whole suffered defeat. The alarming, one-dimensional shadow of the West spread across the globe like the discoloration on a corpse, triumphing over the “flowering complexity” of peoples, cultures, and civilizations, and infecting them with the malady of the flat, bourgeois end of history.

The two types of ideocracy to which the Eurasianists paid such immense attention collapsed precisely as a result of the things they had seen and uncovered: neither communism nor fascism possessed a sufficiently anagogic component, and no matter how unimportant this may have seemed to the political pragmatists, no historical edifice would remain standing for very long without it.

Today, we live in an age in which Europe and its most advanced, monstrous incarnation, the United States, are seeing the final stage of their civilizational victory over Mankind. This is a time when the last bastions of even partial ideocracy have fallen, when Eurasia – as a culture, state, and ideal – has fallen to the pressure of the alternative pole of history.

Only today are we able to properly appreciate the ingenuity of Eurasianism’s founders, taking Nikolai Sergeevich Trubetzkoy as the prime example. Even if tragically belated, he is nonetheless finally getting the recognition he deserves.

The Eurasianists have passed on to us a robust, logically complete, and surprisingly attractive ideal, a national worldview of the grandest scale, of many dimensions, and open to development in all directions. Eurasianism is, in its essence, profoundly patriotic, while containing an intentionally active inoculation against degeneration into vulgar chauvinism. It is a worldview which embraces modernism, the harshness of the avant-garde, and the social technologies of the Bolsheviks, but which casts away any entrancement with economic, materialistic formulae. Eurasianism is a profoundly Christian and Orthodox worldview, but one which has overcome the two centuries of synodal alienation and formal bureaucracy instituted by Patriarch Nikon at the outset of the schism, and which remains open to creative and tolerant dialogue with other traditionally Eurasian confessions.

The most avant-garde methodologies that have since become the basis of purely modern analysis were first put into action by the Eurasianists. They were the first to work out the principles of such disciplines as Russian geopolitics (Petr Savitsky), Russian ethnology (which would later receive brilliant elaboration at the hands of Lev Nikolaevich Gumilev), Russian structural linguistics (structuralism), Russian sociology (particularly as regards the theory of the elites), and much else.

We cannot demand from the historical Eurasianists the answer to all of the questions that face us today, but we must be infinitely grateful to them for having entrusted to us a treasury of strikingly true intuitions, the development of which – through modernizing and enriching them with the latest data and technologies drawn from elsewhere – is today our most pressing task.

Geopolitics, sociology, structuralism, depth psychology, Traditionalism, and the history of religions were all actively developed over the 20th century by an entire constellation of ingenious authors, but we would not succeed in adequately applying their discoveries to our own Russian experience if not for the gigantic theoretical leap carried out by the Eurasianists. And, with their help, everything is gradually falling into its proper place, set within its appropriate national and historical context, and is beginning to shimmer with new light.

Eurasianism is more relevant today than ever before. It is not a thing of the past. It is a project. It is the future. It is an imperative. It is our common task.

You should read the following article by Roman Dmowski, father of modern Poland, on the same topic: https://paulszymanski.substack.com/p/the-danger-to-the-west?r=1lnrkn